You Owe Me Five Shillings

“You owe me five shillings,”

Say the bells of St. Helen’s.

“When will you pay me?”

Say the bells of Old Bailey.

“When I grow rich,”

Say the bells of Shoreditch.

“When will that be?”

Say the bells of Stepney.

“I do not know,”

Says the great Bell of Bow.

“Two sticks in an apple,”

Ring the bells of Whitechapel.

“Halfpence and farthings,”

Say the bells of St. Martin’s.

“Kettles and pans,”

Say the bells of St. Ann’s.

“Brickbats and tiles,”

Say the bells of St. Giles.

“Old shoes and slippers,”

Say the bells of St. Peter’s.

“Pokers and tongs,”

Say the bells of St. John’s.

Origins

This rhyme belongs to the wider family of Oranges and Lemons verses — playful jingles that link London’s parish churches to the sound of their bells. The best-known version (“Oranges and lemons, say the bells of St. Clement’s”) first appeared in print around 1744, but many variations grew alongside it.

You owe me five shillings is one such offshoot. In older collections, the opening line is more often “You owe me five farthings,” which fits better with the small change of everyday London life. The “five shillings” version may have crept in later through mishearing or regional retelling. Either way, the heart of the rhyme stayed the same: the bells are given voices, each one repeating a phrase that reflected local markets, trades, or just the bustle of daily commerce.

Meaning

At its core, this rhyme is less about theology than about street life. Each bell speaks in rhyme, and what it says often mirrors the trades or associations near the church:

-

St. Martin’s mentions coins (“halfpence and farthings”).

-

Whitechapel, long tied to fairs and fruit sellers, calls out “two sticks in an apple,” a reference to toffee apples.

-

St. Ann’s sings of “kettles and pans,” hinting at coppersmiths or tinkers.

-

Others rattle off common, everyday goods — tiles, slippers, pokers, tongs.

Together they form a kind of sonic map of London, where every neighborhood and parish had its own sound, its own commerce, and its own place in memory. Children could chant it like a game, while adults heard echoes of the real city around them.

Cultural Background

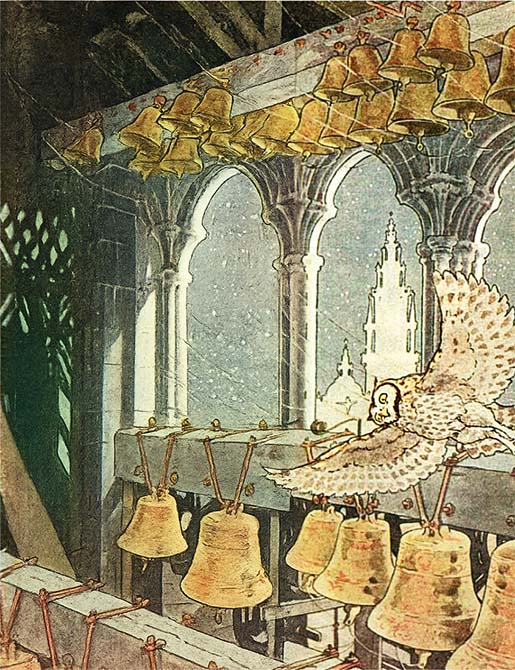

For Londoners, bells weren’t abstract — they were everywhere. They marked the hours, rang for weddings and funerals, tolled during executions, and carried across rooftops in a way that fixed them in memory. Attaching words to the bells gave each church an identity, easy to remember and pass on.

The debt theme in the opening lines — “you owe me five shillings/farthings… when will you pay me?” — was also very real. In 18th-century London, small debts were part of daily life, and debtors’ prisons loomed in the background. It’s no wonder children picked up on this adult anxiety and turned it into sing-song verse.

At the same time, these rhymes were playful. They weren’t sermons; they were a way of making sense of a noisy city through rhythm and repetition. Some versions even became children’s games, where players would pass under arches made by clasped hands until the “bells” trapped someone.

Dozens of versions exist. Some start with “five farthings,” others with “five shillings.” Some feature fewer bells, some more. Whitechapel’s line alone has shifted from “two sticks and an apple” to “pancakes and fritters.” That flexibility shows how oral tradition adapted the rhyme to different neighborhoods and generations.

The most famous short version — “Oranges and lemons, say the bells of St. Clement’s” — eventually overshadowed longer forms like this one, but both belong to the same tradition.