When I Was a Little Boy I Lived by Myself

When I was a little boy I lived by myself,

And all the bread and cheese I got I put upon a shelf;

The rats and the mice, they made such a strife,

I was forced to go to London to buy me a wife.

The streets were so broad and the lanes were so narrow,

I was forced to bring my wife home in a wheelbarrow;

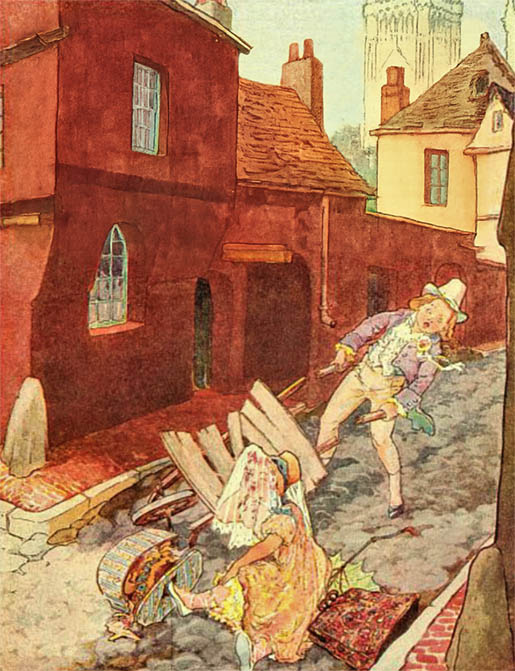

The wheelbarrow broke and my wife had a fall,

And down came the wheelbarrow, wife and all.

Origin

The rhyme When I Was a Little Boy I Lived by Myself has been around for a very long time. The earliest printed version shows up in Mother Goose’s Melody, published around 1765. Later, in the mid-1800s, it appeared again in books for children such as Harry’s Ladder to Learning. Some copies even begin with the line “When I was a bachelor…” instead of “little boy.” That tiny shift makes it sound less like a child’s tale and more like a playful story about a grown man who cannot quite manage his own household. From England, the rhyme spread, and it soon found its way into American collections, too. In folk tradition, people sometimes stretched the story into a longer ballad or sang it with nonsense refrains.

Meaning

This rhyme is really a chain of blunders strung together for laughs. First, the boy loses his food to rats, then he hurries off for a wife, then he carts her home in the most ridiculous way possible — a wheelbarrow. And of course, it all ends in a crash. Kids would have loved the nonsense of it: every step just makes things worse until everything topples over. But grown-ups might have chuckled for a different reason. It feels like a poke at rushing through life, making bad decisions, and paying the price. You can almost hear an old neighbor shaking his head and saying, “Well, that’s what you get for being in such a hurry.” It’s not a tidy moral, more of a knowing smile at how people — young or old — stumble into their own messes.

Allegory

In some tellings, the wheelbarrow scene isn’t even the end. The poor fellow keeps swapping things away—first a horse for a cow, then the cow for a calf, and so on—until he’s standing there with empty hands. It’s the same downward spiral you find in the story of Hans in Luck, where the hero somehow manages to smile while trading treasure for trinkets.

A few collectors also noticed that certain versions slip in the name “Jack Straw.” That’s not just a random name. Jack Straw was one of the leaders of the Peasants’ Revolt in 1381, when angry farmers marched on London. Was the rhyme poking fun at him? Or quietly cheering him on? Nobody can say for sure, but the possibility is tempting. Then there’s the Tom Thumb angle. If the husband was no bigger than a thumb, as in the old fairy tale, a wheelbarrow would be the only practical way to cart home a normal-sized bride. None of these theories can be nailed down, but together they show just how far people are willing to stretch a short, silly rhyme into a story with teeth.

A few collectors also noticed that certain versions slip in the name “Jack Straw.” That’s not just a random name. Jack Straw was one of the leaders of the Peasants’ Revolt in 1381, when angry farmers marched on London. Was the rhyme poking fun at him? Or quietly cheering him on? Nobody can say for sure, but the possibility is tempting. Then there’s the Tom Thumb angle. If the husband was no bigger than a thumb, as in the old fairy tale, a wheelbarrow would be the only practical way to cart home a normal-sized bride. None of these theories can be nailed down, but together they show just how far people are willing to stretch a short, silly rhyme into a story with teeth.

To modern ears, the rhyme sounds absurd. But for people in earlier centuries, the details would have rung true. Bread and cheese were cheap, filling, and in every kitchen—and just as quickly ruined by a night of rats or mice. Everyone knew that frustration. Travel wasn’t much better. Roads were often muddy tracks, narrow enough that you could barely get a cart through. So while the image of a man wheeling home his bride is funny, it isn’t completely outside the realm of reality.

And then there’s the humor aimed at bachelors. Unmarried men were often teased as hopeless cases, unable to keep a household running until marriage forced them into order. So while children laughed at the pratfall of a wife tumbling out of a wheelbarrow, adults probably smirked for another reason: it was a neat reminder of how fragile domestic life could be. That blend—part nonsense, part lived experience, and part gentle mockery—is why the rhyme lasted. It gave kids their slapstick fun and adults their knowing chuckle. That double edge is what carried it from one century to the next.