Hark! Hark! The Dogs Do Bark

Hark! Hark!

The dogs do bark,

The beggars are coming to town;

Some in rags,

Some in tags,

And some in velvet gown.

Versions

Most common version (late 18th century onward):

Hark! hark! the dogs do bark,

The beggars are coming to town;

Some in rags, some in jags,

And one in a velvet gown.

Variation with “tags” (popular in American editions):

Hark! hark! the dogs do bark,

The beggars are coming to town;

Some in rags, some in tags,

And some in a silken gown.

Extended version (with second verse attached later):

Hark! hark! the dogs do bark,

The beggars are coming to town;

Some in rags, some in jags,

And one in a velvet gown.

Some gave them white bread,

And some gave them brown;

Some gave them a good beating,

And sent them out of town.

Origins

The cry “Hark! hark! the dogs do bark” was already old in Shakespeare’s day — he dropped the phrase into The Tempest around 1610. A cheeky song printed in 1672 also began with it, which tells us it had become part of the sound of English streets. But the form children know today — with beggars, rags, and velvet — doesn’t appear in print until the late 1700s. It turns up first in Tommy Thumb’s Song Book (1788) and then quickly spread into anthologies like Gammer Gurton’s Garland. By 1833, it was crossing the Atlantic in The Only True Mother Goose Melodies and being recited in American nurseries.

One curious clue in the verse may point even further back. The word “jags” originally referred to the slashes and decorative cuts in Tudor clothing. By the 18th century, it was mostly taken to mean tatters. So when the rhyme says “some in rags, some in jags,” it could be echoing both poverty and fashion at once. That little detail has led some to argue the rhyme might date to Tudor times, centuries before it reached print.

Meaning

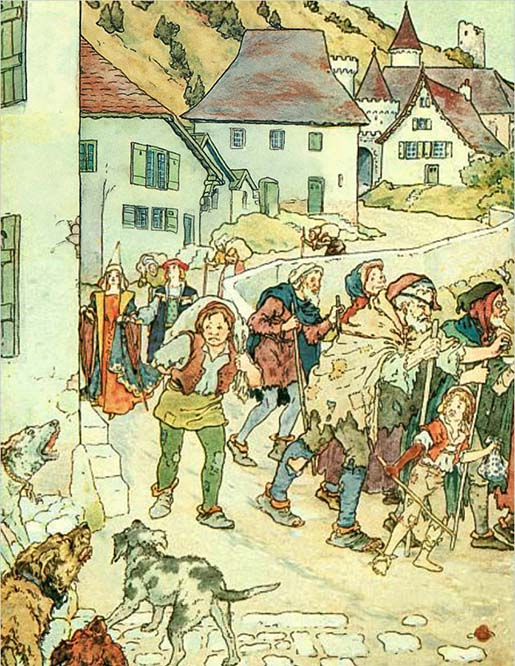

At face value, the rhyme is simple: beggars are arriving, the dogs are barking, and their clothes are a mixed bag — from rags and scraps to one surprisingly fine velvet gown. Children could picture it instantly. It’s part funny, part strange, and very easy to chant.

But adults have often seen satire hiding under the surface. Theories abound:

-

After Henry VIII shut down the monasteries, monks forced into the streets may be the “beggars in rags,” while a high-ranking clergyman kept his velvet.

-

During the Glorious Revolution of 1688, William of Orange’s foreign followers were sneered at as “beggars” — some poor soldiers, some richly dressed lords.

-

Others pointed to George I’s Hanoverian courtiers, mocked as greedy outsiders feeding off England.

And, of course, some argue it’s not political at all. It could simply be describing what children really saw: poor wanderers heading into town, barking dogs chasing them, and one out-of-place figure in fine clothes. That contrast between ragged and rich is what makes the rhyme stick.

In the days before welfare, beggars were everywhere. Towns made rules about them, sometimes giving food, sometimes whipping them out of sight. Dogs barking at strangers would have been a common scene in any village. Children knew that sound and sight well, so the rhyme rang true to daily life.

In the days before welfare, beggars were everywhere. Towns made rules about them, sometimes giving food, sometimes whipping them out of sight. Dogs barking at strangers would have been a common scene in any village. Children knew that sound and sight well, so the rhyme rang true to daily life.

The words themselves show how language shifted. “Rags and jags” once suggested a mix of poverty and odd finery, while “tags” — used in American versions — was a more familiar word for scraps of cloth. And the velvet gown? Velvet was the fabric of judges, bishops, and nobles. A beggar in velvet was laughable, but also a reminder that fortune could flip.

By the Victorian era, this rhyme was everywhere. Kate Greenaway, Walter Crane, and Randolph Caldecott all illustrated it, often showing dogs snapping at ragged men while one proud figure strutted in velvet. Their pictures cemented the contrast and made the rhyme even more vivid for children.

Writers couldn’t resist it either. L. Frank Baum spun it into a whole story, How the Beggars Came to Town (1897), with lush illustrations by Maxfield Parrish. Humorist James Thurber later echoed its cadence in his book The 13 Clocks. Even Beatrix Potter slipped its rhythm into her stories.