Bonny Lass, Pretty Lass

Bonny lass, pretty lass,

Wilt thou be mine?

Thou shalt not wash dishes

Nor yet serve the swine.

Thou shalt sit on a cushion

And sew a fine seam,

And thou shalt eat strawberries,

Sugar and cream.

Not every nursery rhyme is nonsense or slapstick. Some sound more like tiny love songs. Bonny Lass, Pretty Lass is one of those. It paints a picture of courtship where a suitor promises his “bonny lass” a life free of drudgery — no washing dishes, no feeding pigs, only soft cushions, fine sewing, and bowls of strawberries with cream.

Origins

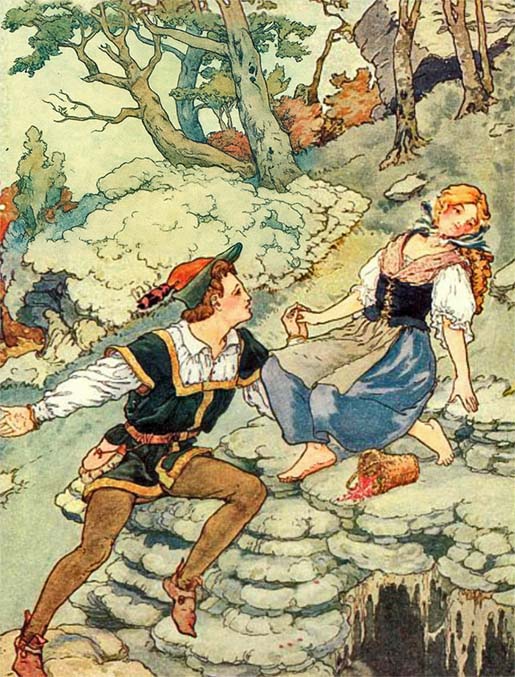

This verse has been around for centuries. The way it’s worded — wilt thou be mine, thou shalt — makes it feel older than the books that finally captured it in the 1800s. People were probably singing or reciting it long before, passing it down like a little courting song. In Scotland, you sometimes find “canny lass” in place of “bonny lass,” showing how the words shifted with the region. By the late Victorian era, it had become part of Mother Goose, with illustrators like Kate Greenaway giving it pictures of graceful young women in ribbons and gowns. The rhyme wasn’t meant to be nonsense — it was closer to a short ballad of affection.

Meaning

On the surface, it’s sweet and simple: a suitor trying to win over a girl with promises of comfort. But tucked in there is a glimpse of class and gender expectations. Washing dishes and feeding pigs were the “low” chores of a household. To be lifted above them meant entering a higher, softer world. The strawberries and cream aren’t just dessert — they’re a symbol of luxury, something special in Victorian England where cream was rich fare and strawberries were seasonal treats.

For children hearing it, though, the rhyme was less about courtship and more about the delicious image of strawberries and sugar. That line alone was enough to keep it memorable.

In Victorian nurseries, this rhyme stood out. While plenty of rhymes were about tumbles, spills, or funny accidents, Bonny Lass, Pretty Lass sounded calmer, almost like a lullaby. Parents might chant it softly, or children might recite it while play-acting fancy lives. The picture it painted — no dirty chores, just sewing by the fire and eating sweet berries — was an appealing dream in a world where real housework was endless. The sewing on a cushion reflected the era’s idea of “proper” accomplishments for a young lady, while the strawberries and cream were the ultimate treat. Illustrators leaned into this, often drawing an idealized maiden, needle in hand, with a bowl of fruit at her side.

In Victorian nurseries, this rhyme stood out. While plenty of rhymes were about tumbles, spills, or funny accidents, Bonny Lass, Pretty Lass sounded calmer, almost like a lullaby. Parents might chant it softly, or children might recite it while play-acting fancy lives. The picture it painted — no dirty chores, just sewing by the fire and eating sweet berries — was an appealing dream in a world where real housework was endless. The sewing on a cushion reflected the era’s idea of “proper” accomplishments for a young lady, while the strawberries and cream were the ultimate treat. Illustrators leaned into this, often drawing an idealized maiden, needle in hand, with a bowl of fruit at her side.