Girls and Boys Come Out to Play

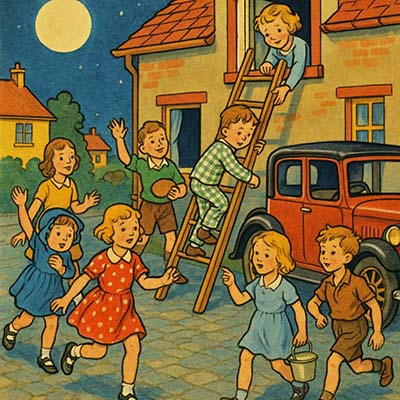

Girls and boys come out to play,

The moon doth shine as bright as day;

Leave your supper and leave your sleep,

And come to your playfellows in the street.

Come with a whoop, and come with a call,

Come with a good will or not at all.

Up the ladder and down the wall,

A penny loaf it will serve us all.

You find milk, and I'll find flour.

And we'll have a pudding in half an hour.

Origins

This little verse has been around for a very long time. It first showed up in print in the early 1700s, and by 1744 it had a place in Tommy Thumb’s Pretty Song Book — one of the very first collections of nursery rhymes ever published. From there, it spread quickly and by the Victorian era, it was a household favorite.

The words have shifted here and there over the years. Sometimes it begins “Boys and girls” instead of “Girls and boys.” Sometimes it promises a “half-penny roll” instead of a “penny loaf.” But the spirit of the rhyme hasn’t changed: it’s always been a call for children to drop what they’re doing and run outside together.

Meaning

At its heart, this rhyme is exactly what it sounds like: an invitation to come out and play. The moon is shining, friends are waiting, and even supper and sleep can wait a little longer.

But tucked inside are glimpses of the past. In earlier times, many children worked during the day. Nighttime — especially under a bright moon — was sometimes the only chance they had to play freely. The rhyme’s talk of climbing ladders and slipping over walls suggests mischief as much as it does fun. And the penny loaf, the milk, and the flour reflect a child’s way of imagining a grand feast out of the simplest foods.

There’s a touch of magic woven through the lines. When the rhyme says, “The moon doth shine as bright as day,” it isn’t just pointing out the weather — it’s giving the night a kind of spell. Under that silver light, the streets feel different, almost secret. Children could imagine they’d slipped into another world, one where bedtime didn’t matter and play could carry on as long as the moon would keep watch.

This was a true street rhyme. It wasn’t sung in classrooms or read in fancy books at first — it was shouted from doorsteps and alleyways to gather a crowd of children once the sun went down. In an age before electric lights, a clear moonlit night really did feel like daylight, and children took advantage of it.

This was a true street rhyme. It wasn’t sung in classrooms or read in fancy books at first — it was shouted from doorsteps and alleyways to gather a crowd of children once the sun went down. In an age before electric lights, a clear moonlit night really did feel like daylight, and children took advantage of it.

Later on, Victorian illustrators like Walter Crane gave the rhyme a more polished look, showing happy children in moonlit scenes. Folklorists such as James Orchard Halliwell recorded it as part of England’s growing nursery tradition, giving a permanent place to what was once just a playful chant.