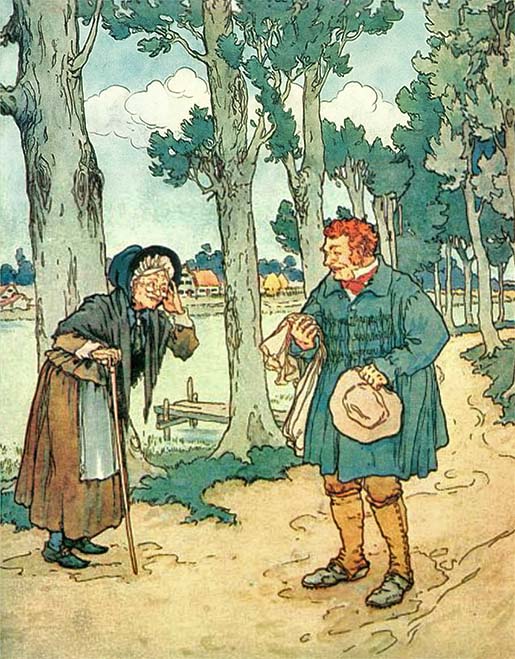

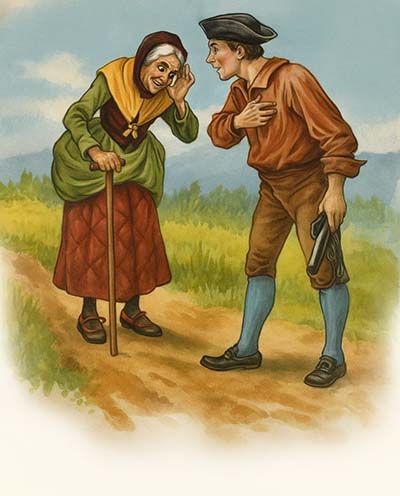

Old Woman, Old Woman, Shall We Go A-shearing?

“Old woman, old woman, shall we go a-shearing?”

“Speak a little louder, sir, I'm very thick o’ hearing."

“Old woman, old woman, shall I kiss you dearly?”

“Thank you, kind sir, I hear very clearly.”

This is one of those rhymes that feels more like a joke passed around the village green than a solemn piece of folklore.

It was already in print by the 1800s, but you can tell it had a life before books. It’s short, it rhymes cleanly, and it gets its laugh in just four lines.

The setup is simple: when the man suggests hard work — shearing sheep, or sometimes reaping or haymaking in other versions — the old woman suddenly goes deaf. But the moment he offers affection, her ears are working perfectly. The humor is gentle, and it probably made people chuckle in the same way a good one-liner does today.

That’s the charm: the rhyme isn’t lofty or moralizing, just a quick comic exchange. It’s the kind of thing you can imagine neighbors saying to each other during farm work, then later parents turning into a rhyme for children.

Meaning

The meaning is light and playful. Work gets ignored. Love gets heard loud and clear. Kids liked the rhythm and the funny twist, while adults smiled because the joke rang true — people often “hear” what they want to hear. There’s no lesson hiding underneath.

The meaning is light and playful. Work gets ignored. Love gets heard loud and clear. Kids liked the rhythm and the funny twist, while adults smiled because the joke rang true — people often “hear” what they want to hear. There’s no lesson hiding underneath.

Call-and-response rhymes like this worked beautifully in everyday life. Imagine a man calling out across a sheep field, and an old woman firing back her reply. Or picture it as a game in the nursery: a parent putting on a mock scowl, cupping a hand to the ear, and grumbling, “I’m very thick o’ hearing.” Then, with perfect comic timing, they perk up and answer the kiss question in a clear, eager voice.