Little Robin Redbreast

Little Robin Redbreast sat upon a tree,

Up went the Pussy-Cat, and down went he,

Down came Pussy-Cat, away Robin ran;

Says little Robin Redbreast: “Catch me if you can!”

Little Robin Redbreast jumped upon a spade,

Pussy-Cat jumped after him, and then he was afraid.

Little Robin chirped and sang, and what did Pussy say?

Pussy-Cat said: “Meow”, and Robin flew away.

The rhyme has been around a long time, and the robin hasn’t always come out looking so clever. In Tommy Thumb’s Pretty Song Book of 1744 — the very first nursery rhyme collection in English — it looked like this:

Little Robin Red breast,

Sitting on a pole,

Nidde, noddle went his head,

And poop went his hole.

Origins

The very first print appearance in 1744 tells us this rhyme is almost three centuries old, but its style points to something even older. The robin was one of the most common birds in English gardens, and the cat one of the most common predators. It was only natural that children’s verses would put them together.

What’s striking is how the rhyme kept shifting. Parents, teachers, and editors clearly reshaped it for their audiences — trimming rough lines, adding more action, and building it into a tiny drama with a beginning, middle, and cheerful end.

Meaning

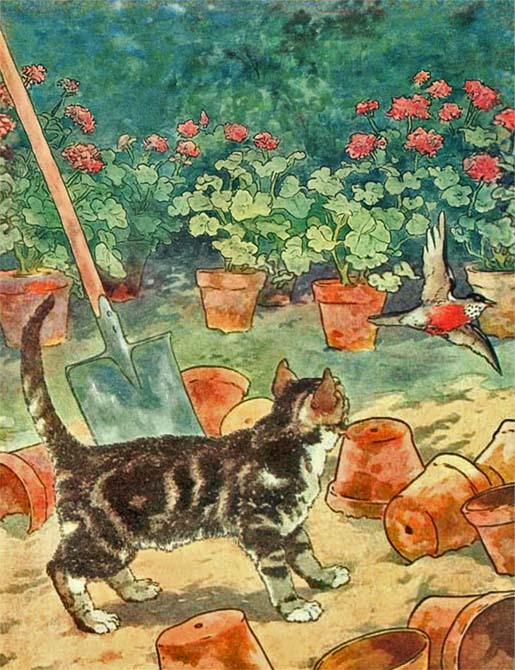

There isn’t a hidden lesson here. It’s a miniature chase story. A bird perches, a cat leaps, and the robin flies away taunting, “Catch me if you can!” In the second stanza, the chase is repeated around the spade, ending with Pussy left meowing on the ground.

There isn’t a hidden lesson here. It’s a miniature chase story. A bird perches, a cat leaps, and the robin flies away taunting, “Catch me if you can!” In the second stanza, the chase is repeated around the spade, ending with Pussy left meowing on the ground.

For children, the rhyme’s fun is in the rhythm and the little burst of danger that always turns out well. It’s suspense without harm, and that mix is why the lighter, playful versions survived while the darker endings faded away.

For children, the rhyme’s fun is in the rhythm and the little burst of danger that always turns out well. It’s suspense without harm, and that mix is why the lighter, playful versions survived while the darker endings faded away.

Cultural Background

Rhymes like this were often acted out as fingerplays. A forefinger could be “Robin,” nodding and perching, while another hand played the cat creeping up. Children loved the motions as much as the words. These games turned the rhyme into a performance — half verse, half puppet show — making it memorable across generations.

Illustrators in the Victorian and Edwardian eras helped fix the rhyme in its gentler form. Their drawings usually showed a plump robin and a wide-eyed cat, more comic than threatening, which matched the playful tone families preferred for nursery use.